When CRM Customization Becomes Vendor Lock-In

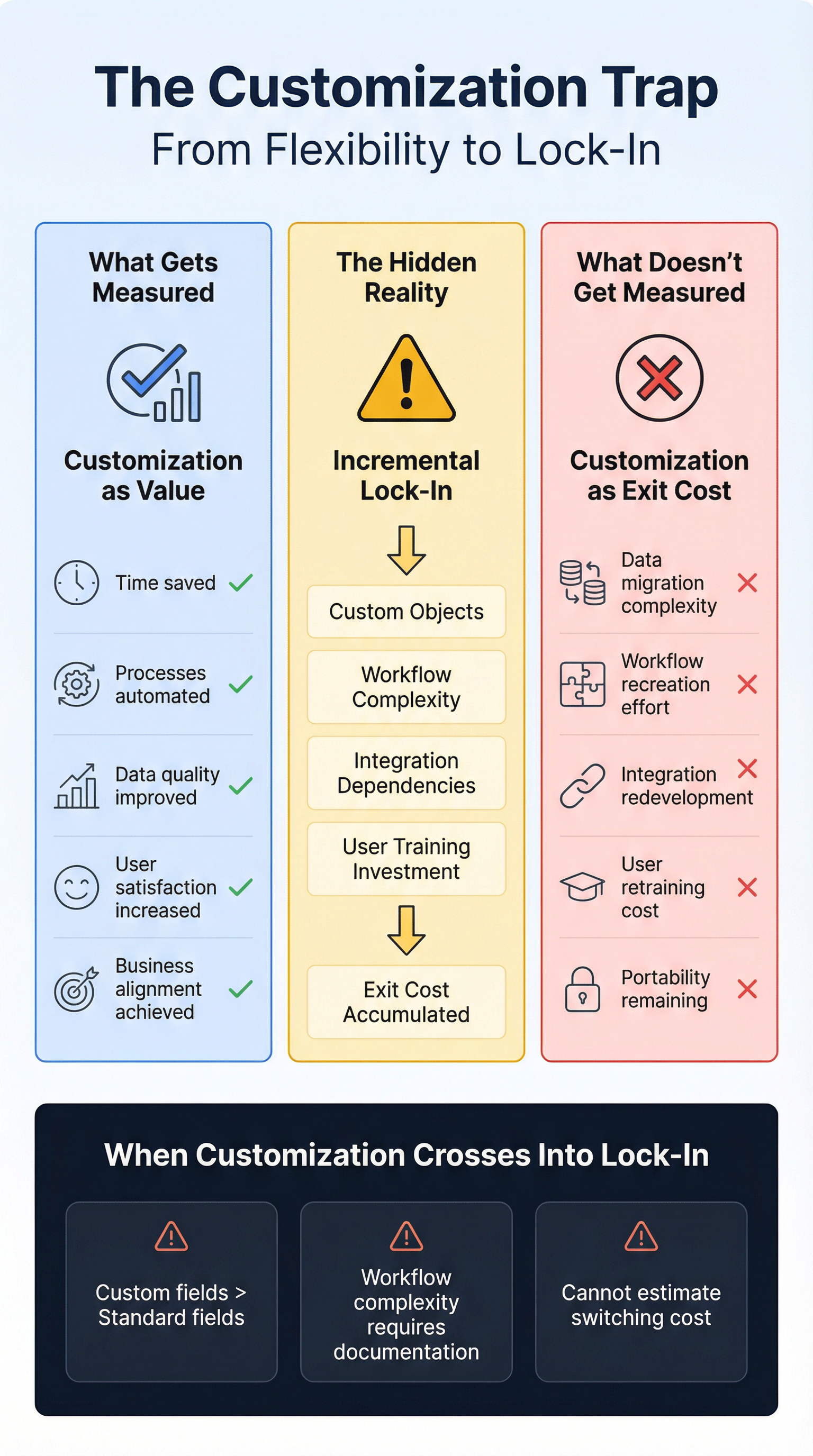

Organizations measure CRM customization as value delivered but fail to measure it as exit cost accumulated. Every layer of customization creates irreversible dependency that only becomes visible when you need to leave.

# When CRM Customization Becomes Vendor Lock-In

When procurement teams evaluate CRM platforms, customization capabilities rank high on the requirements list. The ability to tailor fields, workflows, automations, and integrations to match unique business processes is positioned by vendors as flexibility—a feature that distinguishes enterprise-grade systems from rigid, one-size-fits-all solutions. Organizations invest months configuring their CRM to reflect how they actually work, encoding years of institutional knowledge into custom objects, validation rules, and automated processes. This customization is celebrated internally as value delivered, as evidence that the system truly serves the business rather than forcing the business to conform to the system.

Yet beneath this narrative of flexibility lies a mechanism that silently transforms choice into constraint. Every custom field added, every workflow automated, every integration built creates a dependency that cannot be easily replicated outside the vendor's ecosystem. By the time organizations recognize they are locked in, they have embedded so much business logic into vendor-specific configurations that switching platforms would require not just data migration but complete re-engineering of processes that have evolved over years. The customization that made the CRM valuable has made it irreplaceable.

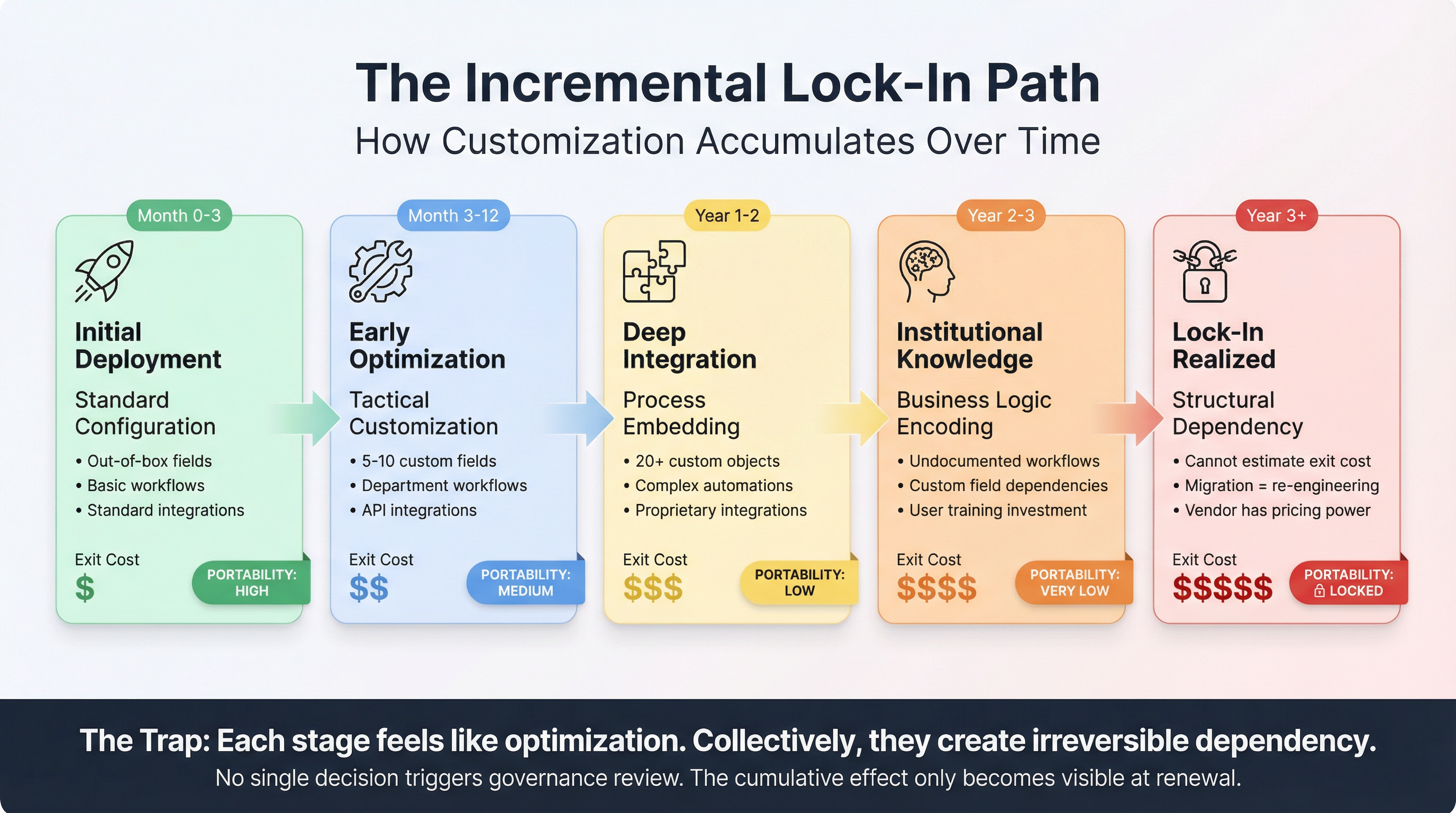

This is not a story about reading contract fine print or negotiating better exit clauses. It is a story about how the incremental decisions made during CRM operation—decisions that feel like optimization—accumulate into structural dependencies that only become visible when the organization needs to change direction. The trap is not set during procurement. It is set during use.

## The Customization Paradox: Value and Dependency as Two Sides of the Same Coin

The appeal of CRM customization rests on a straightforward premise: generic software cannot accommodate the specific ways different organizations manage customer relationships. A manufacturing company tracking complex multi-year contracts needs different data structures than a subscription software business managing monthly renewals. A field sales organization requires different workflow automation than an inside sales team handling inbound leads. Customization allows the CRM to reflect these differences, making the system more useful and more likely to be adopted by users who see their actual work reflected in the interface.

Vendors understand this dynamic and design their platforms to encourage customization. Salesforce, for example, built its market dominance partly on the promise of infinite configurability—the ability to create custom objects, fields, and relationships that mirror any business model. Microsoft Dynamics offers similar flexibility through its entity framework and Power Platform integration. HubSpot markets its customization capabilities as a way to align the CRM with the customer's growth stage. These are not incidental features. They are core value propositions.

The paradox emerges because the same mechanisms that create value also create dependency. A custom object designed to track partner relationships exists only within the vendor's data model. A workflow automation built using the vendor's proprietary logic engine cannot execute outside that environment. An integration constructed using vendor-specific APIs will not function if the CRM is replaced. The more the system is tailored to fit the organization, the less portable it becomes. Customization and lock-in are not opposing forces. They are the same force viewed from different time horizons.

Organizations measure customization as value delivered—time saved, processes automated, data quality improved. They do not measure it as exit cost accumulated. There is no dashboard showing "portability remaining" or "vendor dependency index." The cost of customization only becomes visible when the organization needs to leave, at which point the cost has already been incurred and cannot be reversed without dismantling years of operational infrastructure.

## The Incremental Lock-In Process: How Dependency Accumulates Without Triggering Review

Vendor lock-in is typically imagined as a procurement-stage decision—a choice made when contracts are signed and systems are selected. In reality, lock-in occurs incrementally, through hundreds of small configuration decisions made long after the initial purchase. Each decision feels rational in isolation. A sales operations manager adds a custom field to track a new product line. A marketing team builds an automation to score leads based on engagement patterns. An integration developer connects the CRM to the company's proprietary quoting system. None of these decisions individually creates lock-in. Collectively, over months and years, they construct a system so intertwined with the vendor's architecture that extraction becomes prohibitively expensive.

This incremental process bypasses the governance mechanisms that organizations use to manage technology risk. Major procurement decisions trigger cross-functional review, vendor evaluation, and executive approval. Configuration changes do not. They are treated as operational adjustments, delegated to department-level administrators who are optimizing for immediate business needs rather than long-term flexibility. By the time the cumulative effect of these changes becomes apparent—typically when a contract renewal approaches or when a new executive questions the platform choice—the organization has built dependencies that would take years and significant budget to unwind.

The absence of measurement accelerates this process. Organizations track CRM adoption rates, data quality scores, and user satisfaction. They do not track customization depth or portability risk. There is no threshold that triggers a review when custom objects exceed a certain number, when workflow complexity reaches a critical level, or when integration dependencies cross into dangerous territory. The system evolves organically, shaped by the immediate needs of users who are solving today's problems without visibility into tomorrow's constraints.

Vendors benefit from this dynamic and design their platforms to encourage it. Customization tools are made accessible to non-technical users through low-code interfaces and drag-and-drop builders. Training programs emphasize how to configure the system rather than how to evaluate whether configuration is the right approach. Success metrics focus on feature utilization—how many custom fields are in use, how many workflows are active—without acknowledging that high utilization also means high dependency. The vendor's incentive is clear: the more deeply the customer customizes, the less likely they are to switch.

## The Hidden Cost Calculation: What Organizations Fail to Measure

When evaluating a customization request, organizations typically perform a cost-benefit analysis focused on immediate return on investment. A proposed workflow automation is evaluated based on time saved, error reduction, and user satisfaction. The cost side of the equation includes development time, testing effort, and ongoing maintenance. What this calculation omits is the exit cost—the future expense of replicating that customization if the organization ever needs to switch platforms.

Exit costs manifest in several forms, none of which appear in standard ROI models. Data migration becomes exponentially more complex as custom fields proliferate, because each field must be mapped to an equivalent structure in the new system. If no equivalent exists—and for highly specific customizations, none will—the data must either be discarded or the new system must be customized to accommodate it, replicating the dependency in a different vendor's ecosystem. Workflow automations built using proprietary logic engines cannot be exported as portable code. They must be manually recreated in the new platform's automation framework, a process that requires not just technical translation but also institutional knowledge of why each rule exists and what business logic it encodes.

Integration dependencies compound the problem. A CRM integrated with ten other systems through vendor-specific APIs requires ten new integrations if the CRM is replaced. Each integration represents development cost, testing effort, and potential downtime during migration. If any of those integrations rely on features unique to the current vendor—real-time data sync, bidirectional updates, complex transformation logic—the replacement integration may not achieve feature parity, forcing compromises in functionality or requiring custom development to bridge the gap.

User training costs are often underestimated. A sales team that has spent three years learning a highly customized Salesforce instance is not simply learning "how to use Salesforce." They are learning a specific configuration of Salesforce that reflects their company's unique processes. Switching to a different CRM means retraining not just on a new interface but on a new way of working, because the new system will not replicate the customizations that shaped their current workflow. This retraining extends beyond initial onboarding. Productivity drops during the transition period as users adapt to unfamiliar processes, and some institutional knowledge encoded in the old system's configuration may be lost entirely if it was never documented outside the system itself.

The total exit cost—data migration, workflow recreation, integration redevelopment, and user retraining—can easily exceed the annual licensing cost of the CRM. For organizations with deep customization, it can exceed the total cost of ownership over the system's entire lifecycle. This cost is rarely calculated upfront because it seems hypothetical. The organization has no immediate plans to switch vendors. But the absence of immediate plans does not eliminate the cost. It simply defers recognition until the cost has already been incurred and can no longer be avoided.

## The Recognition Framework: Identifying When Customization Has Crossed Into Lock-In

Lock-in does not announce itself. There is no moment when an organization suddenly realizes it is trapped. Instead, lock-in reveals itself gradually through a series of symptoms that become harder to ignore over time. Recognizing these symptoms early allows organizations to course-correct before dependencies become irreversible.

The first symptom is the proliferation of custom objects and fields that have no equivalent in standard CRM data models. Every CRM platform includes standard objects—accounts, contacts, opportunities, cases—that represent common business entities. Customization begins when these standard objects are extended with additional fields or when entirely new objects are created to represent entities unique to the business. A small number of custom fields is normal and expected. When custom fields outnumber standard fields, or when custom objects outnumber standard objects, the system has diverged significantly from the vendor's baseline architecture. At this point, any migration to a different platform will require extensive custom development to replicate the data model, because no other vendor's standard objects will align with the current structure.

The second symptom is workflow complexity that cannot be easily documented or explained to someone unfamiliar with the system. Workflows encode business logic—the rules that determine how data flows through the organization and what actions are triggered by specific events. Simple workflows are portable. A rule that says "send an email notification when an opportunity closes" can be recreated in any CRM platform. Complex workflows that chain multiple conditions, invoke external systems, and depend on custom field values are not portable. If a workflow requires a multi-page document to explain, or if the person who built it is the only one who fully understands it, that workflow represents a dependency that will be expensive to replicate elsewhere.

The third symptom is integration architecture that treats the CRM as the system of record for data that logically belongs elsewhere. Integrations should connect systems while preserving clear boundaries about which system owns which data. When the CRM becomes the authoritative source for product catalog data, pricing rules, or customer support ticket history—data that could reasonably live in other systems—the organization has made the CRM central to operations in a way that makes replacement disruptive. This centralization often happens incrementally, as teams find it convenient to store additional data in the CRM rather than maintaining it in separate systems. The convenience is real, but so is the dependency it creates.

The fourth symptom is the inability to answer the question "What would it cost to switch?" without conducting a multi-month assessment. If switching costs cannot be estimated within an order of magnitude—whether the answer is tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, or millions of dollars—the organization has lost visibility into its own dependencies. This lack of visibility is itself a form of lock-in, because it prevents informed decision-making about whether to continue investing in the current platform or begin planning an exit.

## The Path Forward: Decision Criteria for Evaluating Customization Against Flexibility

Avoiding the customization trap does not mean avoiding customization entirely. It means making customization decisions with full awareness of the trade-offs involved and establishing governance mechanisms that prevent incremental lock-in from accumulating unchecked.

The first principle is to favor configuration over customization wherever possible. Configuration uses the vendor's built-in flexibility—choosing which standard fields to display, defining picklist values, setting up standard workflows—without creating dependencies that cannot be replicated elsewhere. Customization extends the platform beyond its standard capabilities, creating structures that are unique to the vendor's architecture. Configuration is portable. Customization is not. When evaluating a request for custom development, the first question should be whether the same outcome can be achieved through configuration alone.

The second principle is to maintain a customization budget—not a financial budget, but a complexity budget that limits how far the system can diverge from the vendor's baseline. This budget might be expressed as a maximum number of custom objects, a maximum ratio of custom to standard fields, or a maximum depth of workflow complexity. The specific metrics matter less than the existence of a threshold that triggers review when customization reaches a level that materially increases switching costs. This budget forces trade-offs. If a new customization would exceed the budget, the organization must either decline the request or retire an existing customization to make room.

The third principle is to design integrations for portability. Integrations should use standard protocols and data formats wherever possible, avoiding vendor-specific features that cannot be replicated in other platforms. When vendor-specific features are necessary, they should be isolated in a translation layer that can be replaced without rewriting the entire integration. This approach increases initial development cost but reduces future migration cost, making it a form of insurance against lock-in.

The fourth principle is to document not just what the system does but why it does it. Customizations encode institutional knowledge—the business logic that determines how the organization operates. If that knowledge exists only in the system's configuration, it cannot be transferred to a different platform without reverse-engineering the current system. Documentation should capture the business requirements that drove each customization, not just the technical implementation. This documentation serves two purposes: it makes future migrations feasible, and it forces clarity about whether each customization is truly necessary or merely convenient.

The fifth principle is to conduct periodic portability assessments that estimate switching costs and identify dependencies that have grown beyond acceptable levels. These assessments should be treated as seriously as financial audits, with executive visibility and accountability for managing risk. If switching costs are increasing faster than business value, the organization is accumulating technical debt that will eventually constrain strategic flexibility.

Ultimately, the goal is not to eliminate vendor dependency but to manage it consciously. Every CRM platform creates some level of lock-in. The question is whether that lock-in is proportional to the value delivered, whether it is increasing at a sustainable rate, and whether the organization retains the option to change direction if business needs evolve. Customization is a powerful tool for making CRM systems more useful. It becomes a trap only when organizations lose visibility into the dependencies they are creating and fail to measure the long-term cost of short-term optimization.

The organizations that avoid this trap are not those that refuse to customize. They are those that customize strategically, with full awareness that every configuration decision is also a commitment—a commitment that may outlast the business conditions that made it seem rational. Recognizing this reality does not eliminate the need for customization. It simply ensures that customization serves the organization's long-term interests rather than constraining them.

For organizations seeking to ground their CRM strategy in a clear understanding of how these systems function and where dependencies originate, examining the fundamental architecture and purpose of [CRM software itself](/articles/what-is-crm-software) provides essential context. Only by understanding what CRM platforms are designed to do—and what trade-offs are inherent in their design—can procurement and IT teams make informed decisions about how much customization is appropriate and when flexibility begins to transform into constraint.