Why CRM Data Migration "Success" Often Means Failure

Migration projects that pass every technical checkpoint still fail to deliver usable data. The disconnect stems from measuring migration by technical completion, not business outcomes.

# Why CRM Data Migration "Success" Often Means Failure

The email arrives on Monday morning: "Data migration completed successfully. Zero errors. All records transferred." The project manager marks the task complete. Three weeks later, the sales team can't find customer histories. Marketing discovers duplicate contacts across campaigns. Finance reports revenue discrepancies between the old and new systems.

This pattern repeats across organizations implementing CRM systems. Migration projects that pass every technical checkpoint still fail to deliver usable data. The disconnect stems from a fundamental misunderstanding: companies measure migration by technical completion, not business outcomes.

## The Validation Theater

Most migration projects follow a familiar script. Teams extract data from the legacy system, map fields to the new CRM, run validation scripts, and execute the transfer. When the process completes without errors, everyone celebrates. The validation scripts confirm that every record transferred, data types match, and required fields contain values.

What these scripts don't catch is whether the data makes sense.

Consider a typical scenario: a company migrates 50,000 customer records from an aging CRM to a modern platform. The validation report shows 100% completion. Every account has a name, every contact has an email, every opportunity has a value. The technical team declares victory.

Then users start working with the data. They discover that "account names" contain inconsistent formatting—some entries use legal entity names, others use brand names, and a few include internal codes. Contact emails pass format validation but include hundreds of inactive addresses. Opportunity values transferred correctly as numbers, but the currency codes didn't map, rendering half the pipeline data meaningless.

The validation scripts checked format compliance. They didn't verify semantic accuracy. This distinction matters because [understanding the full scope of what CRM implementation actually involves](/articles/what-is-crm-software) requires recognizing that data migration isn't a technical exercise—it's a business logic translation project.

## When Field Names Lie

Field mapping appears straightforward on paper. The old system has a "Status" field, the new system has a "Status" field—map one to the other and move on. This approach works until you examine what "Status" actually means in each context.

In one system, "Status" might indicate account health: Active, At Risk, Churned. In another, it might track sales stage: Prospect, Qualified, Customer. Same field name, completely different business logic. When you map these directly, you don't transfer data—you create nonsense.

Organizations consistently underestimate how much semantic drift exists between systems. A "Priority" field in one platform might use High/Medium/Low. The target system might use P1/P2/P3/P4. Direct mapping fails because the scales don't align—what constitutes "High" priority in one system might span P1 and P2 in another.

The problem compounds when fields share names but serve different purposes. "Owner" might mean account executive in the source system and customer success manager in the target. "Region" could refer to sales territory or geographic location. "Type" might classify industry vertical or customer segment.

These misalignments don't trigger validation errors. The data transfers successfully. Users only discover the problem when they try to run reports, build automations, or make decisions based on the migrated information. By then, correcting the issue requires understanding months of business context that wasn't documented during migration.

## The Historical Context Trap

Migration teams often prioritize current data over historical records. The logic seems sound: focus resources on the information users access daily. Historical data can wait, or perhaps doesn't need to migrate at all.

This decision creates invisible problems. Customer relationship management depends on understanding interaction history. When did we last contact this account? What products have they purchased? Which support issues have they raised? How has their engagement changed over time?

Without historical context, every customer relationship starts from zero. Sales reps can't reference past conversations. Support teams lack ticket history. Marketing can't identify engagement patterns. The CRM becomes a contact database instead of a relationship management tool.

The challenge extends beyond missing records. Historical data often carries business logic that only makes sense in temporal context. An opportunity marked "Closed-Lost" six months ago might have reopened under a different deal ID. A contact who changed companies might appear as two separate people. Activities logged under old user accounts might lose attribution when those users no longer exist in the new system.

Organizations discover these gaps gradually. A sales rep prepares for a meeting and can't find notes from previous calls. A support agent handles an escalation without seeing the customer's complaint history. A finance team tries to analyze year-over-year trends and realizes the data only goes back three months.

Research indicates that organizations believe up to one-third of their CRM data may be inaccurate, and 55% of business leaders report lacking trust in their data assets. These trust issues intensify when historical context disappears during migration, leaving teams unable to verify current information against past patterns.

## Schema Drift and Mapping Decay

Systems evolve. The CRM you implemented three years ago doesn't match the one you're migrating from today. Fields get added, renamed, deprecated. Required fields become optional. Dropdown values expand or consolidate. Relationships between objects change.

Most organizations don't track these changes systematically. There's no version control for field definitions, no changelog for schema modifications, no documentation of why certain fields exist or what business rules govern their use. When migration time arrives, teams work from incomplete information.

The mapping exercise becomes archaeological work. Why does this field contain codes instead of names? When did we start using this picklist value? Which fields are actually required versus technically optional but business-critical? Nobody remembers, and the documentation doesn't say.

This knowledge gap creates two problems. First, teams map based on current field names without understanding historical usage patterns. A field that technically accepts text might have always contained numeric codes. A dropdown that allows "Other" might have specific business rules about when that option is valid. Second, teams can't distinguish between fields that matter and fields that exist only for legacy reasons.

The result is mapping debt—accumulated misalignments between how systems are supposed to work and how they actually function. Like technical debt, mapping debt compounds over time. Each unmapped edge case, each semantic misalignment, each undocumented business rule adds friction. Users develop workarounds. Reports require manual adjustments. Integrations break in subtle ways.

Organizations typically discover mapping debt through user complaints rather than systematic review. Someone notices that automated workflows aren't triggering correctly. A report shows unexpected nulls. An integration starts failing intermittently. Each issue requires investigation to determine whether the problem stems from migration mapping, system configuration, or user error.

## Testing Theater and Production Reality

Migration projects almost universally include testing phases. Teams extract a subset of data, run the migration in a sandbox environment, and verify results. When the test succeeds, they proceed to production migration with confidence.

This confidence is often misplaced. Sandbox testing validates that the migration process works—it doesn't verify that the process handles production data correctly. The distinction matters because sandbox data differs fundamentally from production data.

Sandbox environments typically contain clean, simplified datasets. Test accounts have complete information. Relationships follow expected patterns. Edge cases are rare. This clean data passes through migration smoothly, giving teams false confidence that production will work the same way.

Production data accumulated over years of real business operations. It contains incomplete records, duplicate entries, inconsistent formatting, orphaned relationships, and countless edge cases that nobody documented. When this messy reality hits migration scripts designed for clean data, problems emerge.

Some issues surface immediately: records that fail validation, relationships that can't be established, required fields that lack values. These technical failures are actually the best outcome because they force teams to address problems before users encounter them.

More insidious are the silent failures. Records that transfer successfully but lose critical context. Relationships that map technically but don't reflect actual business connections. Values that pass validation but don't mean what they're supposed to mean. These problems don't trigger errors—they just create bad data.

Users discover silent failures gradually, through accumulated frustration. A customer record exists but lacks purchase history. An opportunity shows a value but the currency is wrong. A contact appears active but all their activities are missing. Each discovery erodes trust in the new system and creates pressure to "just check the old CRM" instead of relying on migrated data.

## Measuring Migration by User Outcomes

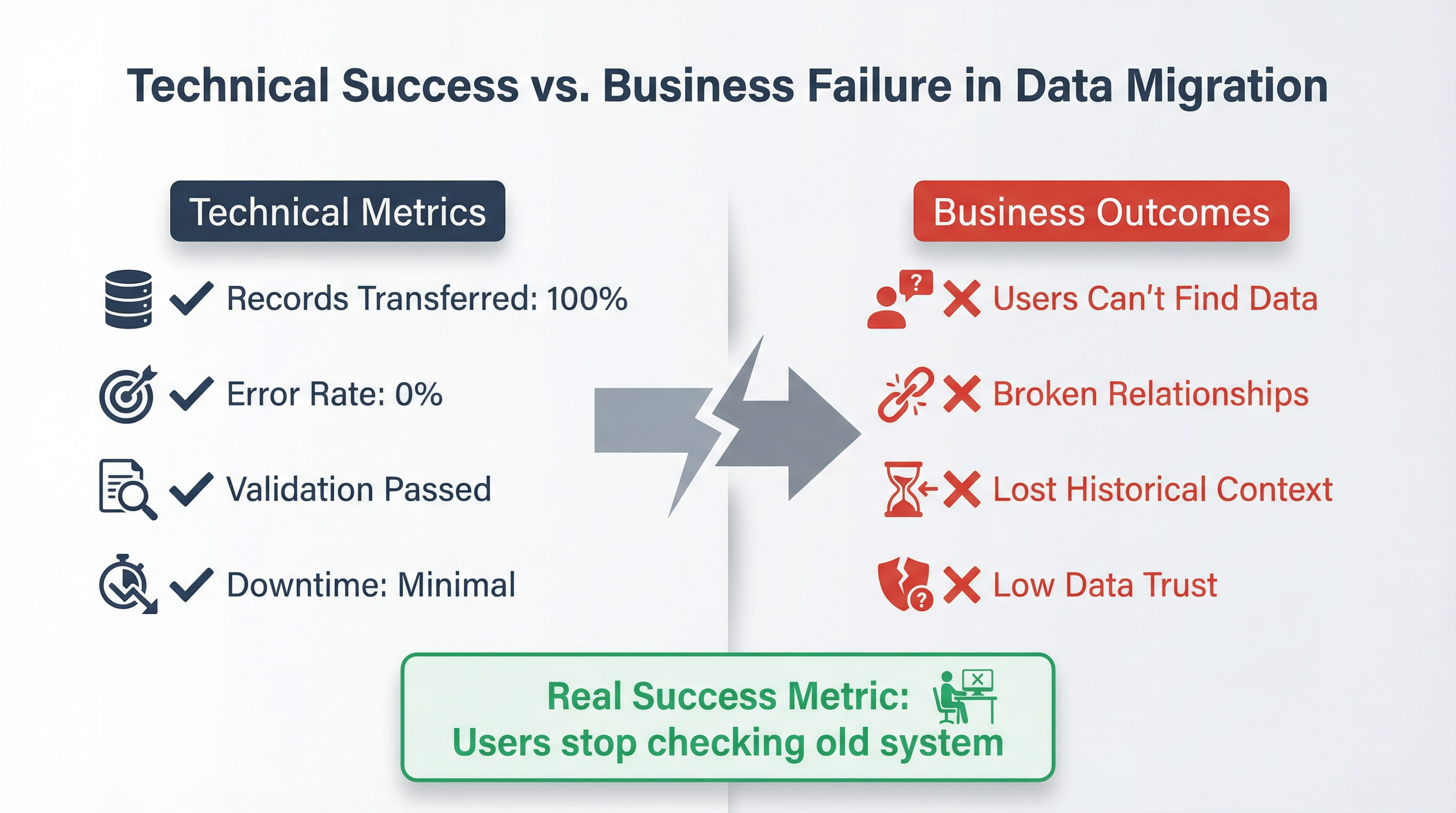

*This framework illustrates the disconnect between technical completion metrics and actual business outcomes in CRM data migration projects.*

The fundamental problem with CRM data migration isn't technical—it's definitional. Organizations measure success by completion metrics (records transferred, error rate, downtime) rather than usability metrics (can users find what they need, does the data support business decisions, do relationships remain intact).

This measurement gap creates a disconnect between project teams and end users. The migration team sees 100% completion and zero errors. Users see missing information, broken relationships, and data they can't trust. Both perspectives are accurate—they're just measuring different things.

Shifting to outcome-based measurement requires different success criteria. Instead of asking "did all records transfer," ask "can sales reps find customer histories." Instead of "did field mapping complete," ask "do automated workflows trigger correctly." Instead of "were there errors," ask "do users trust the data."

These questions are harder to answer because they require observing actual usage rather than checking technical logs. They surface problems that validation scripts miss. They reveal whether migration succeeded at its actual purpose: enabling users to manage customer relationships effectively.

Organizations that adopt outcome-based measurement typically extend migration timelines and increase resource requirements. They run parallel systems longer. They conduct more extensive user testing. They invest in data quality remediation after technical migration completes. These investments feel expensive until you compare them against the cost of failed adoption, lost productivity, and eroded data trust.

The choice isn't between perfect migration and imperfect migration. It's between measuring what's easy to measure and measuring what actually matters. Technical completion is easy to measure. User success requires more effort but delivers more value.

## The Real Success Metric

CRM data migration succeeds when users stop asking to check the old system. When sales reps trust the customer histories they see. When support agents rely on ticket records without verification. When finance accepts revenue reports without manual reconciliation. When marketing builds campaigns using contact data without cleaning it first.

These outcomes don't happen automatically when technical migration completes. They require understanding that data migration is fundamentally a business logic translation project, not a technical data transfer exercise. They demand measuring success by user outcomes rather than completion metrics. They need recognition that "migration completed successfully" and "migration succeeded" are often very different statements.